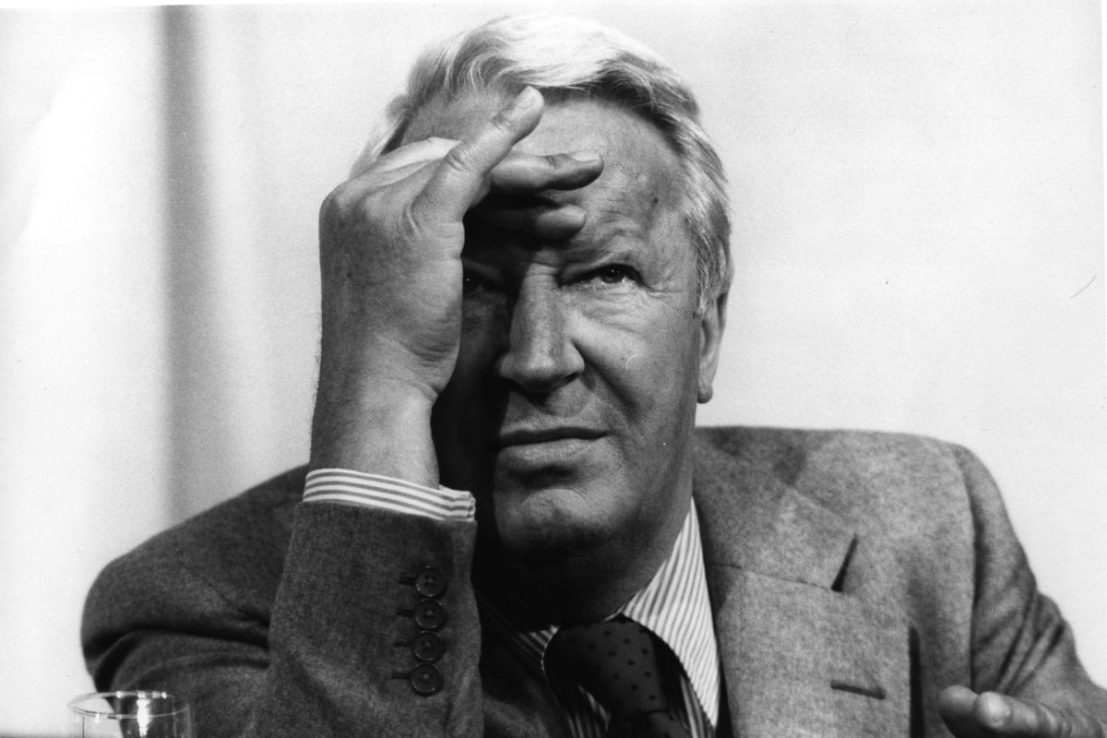

On this day: Edward Heath’s incredible sulk comes to an end

Twenty years ago today, at 7.30 pm on 17 July 2005, Sir Edward Heath died at the age of 89 at his home in Salisbury. He had been Prime Minister for three years and 259 days, 26th of what was then 51 premiers. It was 30 years since he had held office.

He could have been a footnote, jostling in the collective memory with the likes of the Duke of Portland or the Earl of Derby. Yet even his detractors would admit that his tenure in Downing Street, from June 1970 to March 1974, was a critical period of modern British history.

Edward Richard George Heath was not instinctively suited to political leadership. He was stiff, often pompous, had few friends and no small talk. A loner, his passions were music – he was an organ scholar at Balliol College, Oxford, in the 1930s – and sailing: Enoch Powell dismissed the 1970 general election, Heath facing incumbent PM Harold Wilson, as a choice between a man with a boat and a man with a pipe. He was a forgettable speaker, though on form in the House of Commons he had a blunt forcefulness which could be effective.

Heath deserves to be remembered for three reasons. The first is that he became leader of the Conservative Party at all. The second is that he succeeded where Macmillan and Wilson had failed and took the United Kingdom into the European Economic Community. The third is the bitter, three-decade coda to his life, never coming to terms with his replacement by Margaret Thatcher and never admitting he had ever been wrong.

Humble origins

Modern politicians like to parade the ordinariness of their backgrounds. Heath did not, but there is a strong argument that he had come further, socially and economically, than any Conservative leader in the party’s history, and certainly his only challenger is John Major.

Heath was born in Broadstairs in Kent, in the summer of 1916. His father William was a carpenter who built airframes for Vickers and later became a builder, while his mother Edith was a lady’s maid at a time when more than a million Britons were still in domestic service.

The twin platforms of education and military service allowed Heath to prosper. Intelligent, sharp-minded and organised, he won a county scholarship to Balliol, where he met Denis Healey and Roy Jenkins, became president of the Oxford Union and graduated just before the Second World War began. He spent most of the conflict in the Royal Artillery, rising to lieutenant-colonel and launching himself into Conservative politics with that invaluable attribute, a “good war”.

Elected for Bexley in 1950, he became Sir Anthony Eden’s chief whip in 1955 and from 1960 to 1963 he was the Earl of Home’s deputy at the Foreign Office, in charge of the UK’s application to join the Common Market. When Home – by then Sir Alec Douglas-Home MP – relinquished the party leadership in 1965, Heath was shadow chancellor and a leading candidate to replace him. Against Reginald Maudling, the affable former chancellor who was fond of a long lunch, Heath seemed energetic, modern and classless: one obituarist called him “the first Tory leader to have wall-to-wall carpets”.

Into Europe

Heath unexpectedly beat Wilson in the 1970 general election with a majority of 30 seats and could finally turn his attention to his great political passion: Europe. He dominated his cabinet as few Prime Ministers have: Maudling was tired and disenchanted, Douglas-Home as foreign secretary was semi-detached, Quintin Hogg was despatched (back) to the upper house as lord chancellor and Iain Macleod served only a month as Chancellor before his sudden death.

The Conservative Party was broadly but not universally behind the idea of EEC membership, and Enoch Powell engaged in passionate and anguished trench warfare against what became the European Communities Act 1972. Labour was bitterly divided, and the bill only passed its Second Reading by eight votes. But it was granted Royal Assent on 17 October 1972, and the UK acceded to the EEC on 1 January 1973.

For Heath it was the fulfilment of a dream. He had seen the rise of Nazism in the 1930s, meeting Göring, Himmler and Goebbels at a party at the 1937 Nuremberg Rally, and was convinced that political unity was the only guarantee against such evil happening again. It was a view from which he would never resile and on which he would never compromise.

The long goodbye

It was the economy which destroyed Heath’s premiership, and when he asked “Who governs Britain?” at the snap election of February 1974, the electorate decided it was no longer him. But industrial action and poor economic performance were magnified by the Troubles in Northern Ireland and the oil crisis of 1973-74.

By 1975, Heath had lost three of the previous four general elections: 1966, February 1974 and October 1974. Yet he could not accept that he was part of the problem. He was not only aghast but bewildered when Margaret Thatcher, of whom he thought little, ejected him, and he never came to peace with his dethronement. Refusing a peerage, he stayed in the House of Commons for another quarter-century, until 2001, latterly as Father of the House.

He opposed almost everything Thatcher did, his brooding presence on the backbenches earning him the nickname “the Incredible Sulk”. When asked if it was true that he had celebrated her fall in 1990 with the words “Rejoice, rejoice!”, he replied “I said it three times, I think”.

Heath provided a masterclass in graceless retirement, but was cantankerously oblivious. He always believed the Conservative Party, not he, had made a mistake. But he died with the UK’s membership of the European club seemingly assured. In 2005, while Britain was an awkward member of the EU, withdrawal seemed an impossible and incredible idea. But a great deal can happen in 20 years.

Eliot Wilson is a writer